Article:

Each morning, as sunlight peels back the mist from rooftops and birds burst into song, millions of children around the world begin their silent march. They head towards the clang of school bells echoing across cities, towns, and villages—bells not of invitation, but of obligation. With slumped shoulders and heavy backpacks, they enter classrooms where time ticks louder than imagination, where chalk dust mingles with the pressure to perform.

Inside these walls, teachers sprint through syllabi like runners chasing an invisible finish line. They are not racing towards wonder—but away from failure. We must finish the syllabus. We must prepare them for the test In Nairobi, a 14-year-old girl named Amina stares out of a classroom window—not in rebellion, but in longing. Her eyes rest on a jacaranda tree, its purple blossoms trembling like secrets in the wind. In Toronto, Javier refreshes his GPA portal obsessively—every digit a measure of worth, every decimal a doorway or a dead end. In Delhi, young Aarav repeats history dates under his breath like a mantra, memorizing without meaning, trapped in the grind of study, test, forget, repeat.

This quiet disengagement—this invisible ache—isn’t unique. It is global. According to a 2023 UNESCO report, more than 40% of students worldwide feel anxious, alienated, or utterly indifferent to school. Education, once the spark that lit minds, is now, for many, a system that extinguishes wonder.

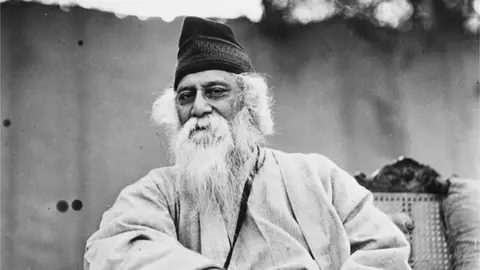

More than a century ago, one man saw the storm coming.

In the rural heart of Bengal, a boy once looked up at the sky—not to calculate it, but to converse with it. That boy was Rabindranath Tagore – poet, philosopher, and the first non-European Nobel Laureate in literature. Tagore saw the colonial school system for what it truly was: a machine built to produce clerks, not creators. It filled minds while emptying souls.

So he dreamed, and then he built, something radically different.

In 1901, he founded Santiniketan—a school under the open sky. Here, learning didn’t begin with bells but with birdsong. Children studied beneath trees, barefoot on earth, their lessons guided by curiosity, not coercion. It was a school without regimentation, without fear, and most profoundly—without walls.

Tagore’s vision was not a utopian fantasy. It was a fierce act of rebellion—against mechanical instruction, against colonial domination, and against the soulless grind of rote learning. His was an education rooted in liberation.

At its heart lay five timeless principles—each more vital today than ever.

The first was learner autonomy. At Santiniketan, education wasn’t something done to the child—it was something born within them. A student could spend the morning writing a poem about the morning mist or tracing the delicate paths of ants across tree bark. They weren’t skipping school. They were school.

Tagore believed that education must begin with freedom. “Don’t limit a child to your own learning,” he said, “for he was born in another time.” He knew: children are not containers to be filled—they are fires waiting to be lit.

Today, this principle finds echoes around the globe. In Amsterdam, students embark on semester-long passion projects—one group designing vertical gardens for urban slums, another programming drones to replant deforested land. These are not privileged anomalies. They are living proof of what happens when we trust students as co-authors of their own learning. Even in traditional classrooms, small shifts—choice-based assignments, flexible reading lists, collaborative research—can awaken ownership and joy.

The second pillar: interest-led exploration. Tagore held curiosity sacred. Education, he believed, should not stifle questions—it should chase them.

At a school in Cape Town, a student spotted a beehive by the fence. That moment birthed an interdisciplinary cascade: science lessons on pollination, discussions on environmental decline, poetry inspired by bees, even a campaign to save local pollinators. For weeks, the beehive was the curriculum.

Educators often say, “My students just don’t care.” But is it apathy—or a response to a system that ignores their questions, their voices, their dreams? Schools don’t need to abandon structure—they just need to make space for wonder. “Wonder Hours,” thematic inquiry weeks, passion-based projects—these can transform the classroom from a cage into a playground for the mind. At a school in Cape Town, a student spotted a beehive by the fence. That moment birthed an interdisciplinary cascade: science lessons on pollination, discussions on environmental decline, poetry inspired by bees, even a campaign to save local pollinators. For weeks, the beehive was the curriculum.

Educators often say, “My students just don’t care.” But is it apathy—or a response to a system that ignores their questions, their voices, their dreams? Schools don’t need to abandon structure—they just need to make space for wonder. “Wonder Hours,” thematic inquiry weeks, passion-based projects—these can transform the classroom from a cage into a playground for the mind.

The third cornerstone was learning through nature. To Tagore, the earth wasn’t just a setting—it was the greatest teacher. Rivers taught rhythm. Trees taught patience. Seasons taught change. At Santiniketan, children learned science not from diagrams, but from the shape of leaves and the song of wind. Nature wasn’t the backdrop. It was the book.

Today, a teacher in Seoul remarked that her students could identify ten phone brands, but not three native trees. This disconnect is more than sad—it’s dangerous. It breeds indifference to a planet in peril. Yet, green shoots are sprouting. Forest Schools in the UK take children outdoors year-round. In Scandinavia, students learn math through gardening, and literature through nature journaling. In cities around the world, schools are reclaiming gardens, holding art classes under open skies, or studying weather patterns in real time. One needn’t have a forest—just a window, a courtyard, a sky is enough.

Then came the arts, which for Tagore were never mere extras. Music, painting, dance, and drama were central to learning—not for decoration, but for development. A child sculpting clay was learning concentration, spatial awareness, emotion, and storytelling. Creativity was not a break from learning—it was learning. Today, as education systems around the world narrow their focus to test scores and measurable outputs, the arts are often the first to be trimmed. Yet research tells another story: arts-integrated learners perform better academically, show higher emotional intelligence, and solve problems with greater flexibility. What if we taught history through theatre, chemistry through color, and math through melody? These aren’t novelties—they are ancient techniques, reborn. The arts speak the language of the soul—and when children are fluent in that language, they grow not only smarter, but wiser.

The final thread in Tagore’s tapestry was cultural and linguistic pluralism. While colonial systems erased identity to create conformity, Tagore’s school celebrated it. Bengali was not forbidden—it was honoured. Folk tales were studied. Local music echoed through campus. Festivals became immersive learning experiences. Even today, millions of children are taught in languages not spoken at home. This isn’t just hard—it’s harmful. It fragments identity and creates invisible barriers to comprehension and confidence. Of course, recreating Santiniketan in today’s context is no easy task. Rigid curricula, exam-centric cultures, underfunded schools, and overworked teachers are real obstacles.

But transformation doesn’t require a revolution—it starts with intention.

A teacher can shift from being a transmitter to a facilitator. A school can introduce project-based learning within set subjects. Assessments can include portfolios, reflections, or even peer reviews. Local communities—elders, artisans, musicians—can become co-educators. The environment can become the classroom.

Tagore reminds us: education must begin with belonging. Let children learn in their mother tongues. Let their history, myths, songs, and stories be part of the syllabus. Only then can learning expand—not by uprooting, but by deepening.

And the world is already moving.

In India, The Riverside School empowers students to solve real-world problems—from recycling systems to public health awareness. In New Zealand, Playcentres let parents and children learn together without rigid curriculums. Finland, admired globally, has woven play, arts, and nature into its national standards with minimal testing and maximal trust.

These aren’t miracles. They are maps.

A teacher in Buenos Aires once whispered, “More than anything, I hope my students leave school still wanting to learn.”

That quiet wish—that humble prayer—captures the very soul of Tagore’s dream.

Not classrooms that crush spirits.

Not schools that churn out scores.

But spaces that awaken the child, in all their curiosity, courage, and creativity.

In an age when artificial intelligence can answer questions in milliseconds, our job is no longer to manufacture knowledge—it is to cultivate wonder. Machines can solve equations. But they cannot write poetry after seeing the moon through tears. They cannot fall in love with a question.

And so, we must ask ourselves:

What if schools had no walls?

What if lessons began with questions, not answers?

What if learning helped us become—not just more informed—but more alive?

In every classroom where a teacher whispers, “What do you wonder today?”

In every school where children study under trees, sing in their own languages, or paint before they memorize—

In every place where learning is joy, not just duty— Tagore’s spirit lives on.

Content Disclaimar

Asia Education Digest publishes articles, interviews, and opinion pieces contributed by educators, leaders, and professionals from across the globe. The views and opinions expressed in this magazine are those of the individual authors and contributors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Asia Education Digest or its editorial team.

While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information at the time of publication, the magazine assumes no responsibility for errors, omissions, or outcomes resulting from the use of this information. Readers are encouraged to verify details independently where necessary.

All content is intended for informational and educational purposes only and should not be considered as professional, legal, or financial advice. Reproduction or distribution of material from this magazine, in whole or in part, without prior written permission from the publisher, is strictly prohibited.

© 2025 Asia Education Digest. All rights reserved.